The Sydney Morning Herald reports:

“Former federal Labor MP Craig Thomson will spend the night behind bars after he was arrested over allegations he facilitated more than 130 fraudulent visa applications over four years, resulting in more than $2 million of financial gains…

“Mr Thomson was arrested at his Terrigal residence on Wednesday and charged with multiple offences, including 19 counts of providing false documents and false or misleading information, five counts of a prohibition on asking for or receiving a benefit in return for the occurrence of a sponsorship-related event, two counts of obtaining a financial advantage by deception and one count of dealing with proceeds of crime.

He was refused bail at Gosford Police Station and his matter will be heard before Gosford Local Court on Thursday.”

Continue reading “Former Labor MP Craig Thomson arrested and remanded over visa fraud allegations”

The Supreme Court of NSW has exercised its inherent jurisdiction to strike off a former federal Labor MP for misappropriation of trade union funds and the criminal and civil convictions which resulted from it.

Craig Thomson was admitted as a lawyer in NSW on 31 March 1995, although he never obtained a practising certificate.

From around 1988, Thomson was employed by the Health Services Union (HSU), initially as an industrial officer in the New South Wales branch.

On 16 August 2002, Thomson was elected as National Secretary of the HSU. Two months later, Thomson established a business account for the HSU National Office in Victoria with the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). He was the only signatory to this account, which included a CBA credit MasterCard with a cash withdrawal facility accessible by PIN. In accordance with HSU policy, that card was only to be used for work-related expenses. Irregularities in the accounts for the card were, however, revealed by an exit audit conducted after Thomson’s resignation as National Secretary.

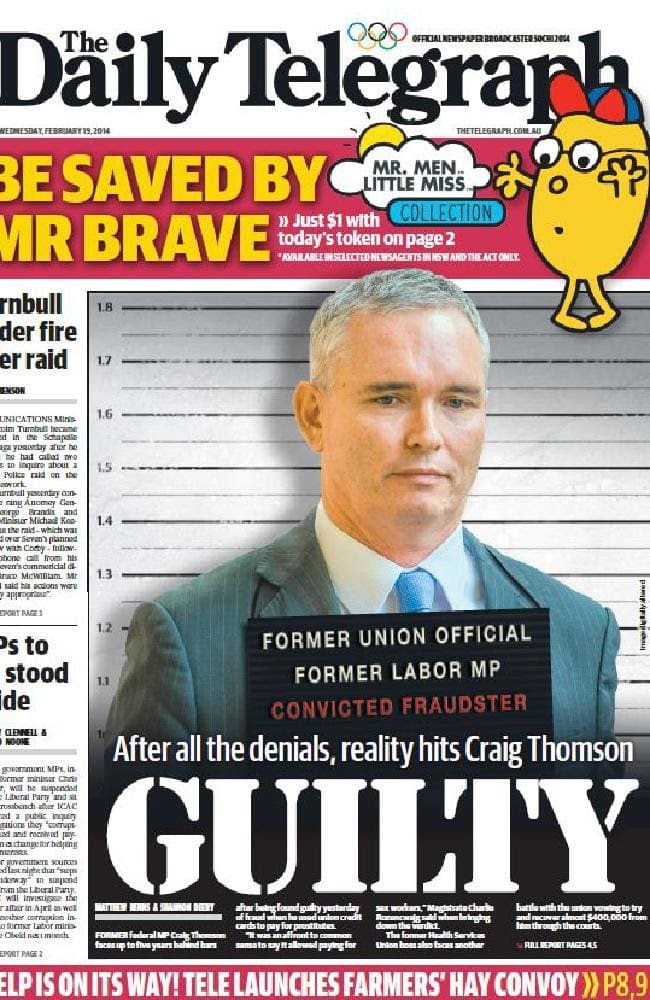

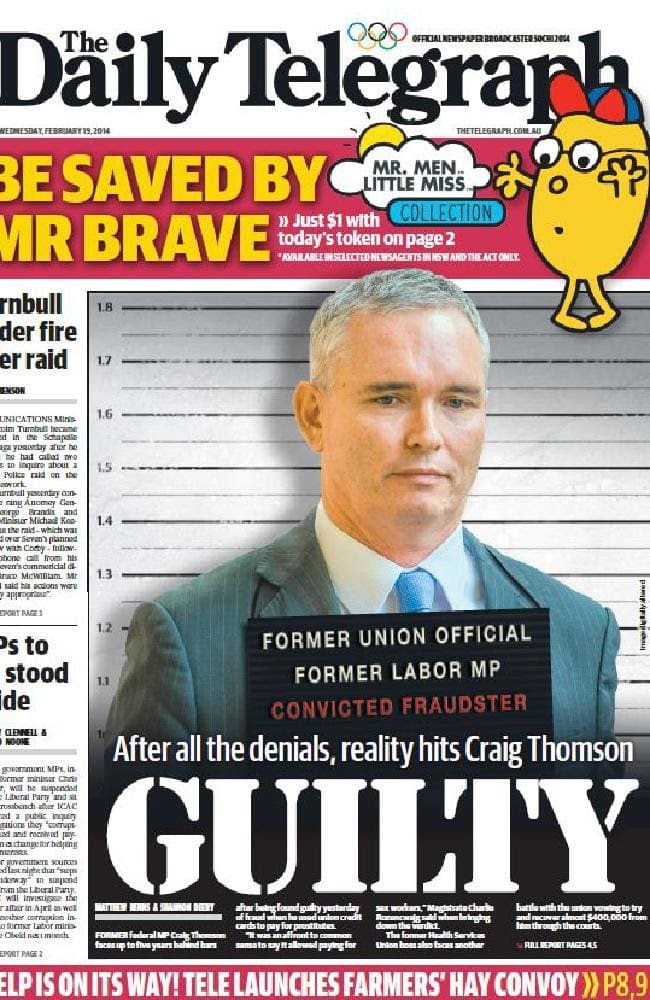

On 24 November 2007, Thomson was elected as a Member of the Federal Parliament for the seat of Dobell. Although re-elected in 2010, public revelations concerning the misappropriation of HSU funds during his time as its Secretary led to him resigning from the Australian Labor Party in about 2012 and losing his seat at the 2013 federal election.

On 15 December 2014, in the proceeding in the County Court, Thomson was found guilty of 12 charges of stealing cash belonging to the HSU, amounting to at least $5,350 over a four-year period from October 2003 to October 2007: Director of Public Prosecutions v Thomson (County Court of Victoria, Judge Douglas, 15 December 2014).

On 17 December 2014, he was convicted and, by way of sentence, ordered to pay an aggregate fine of $25,000 and compensation to the HSU of $5,650: Director of Public Prosecutions v Thomson (County Court of Victoria, Judge Douglas, 17 December 2014). As at 13 June 2018, he had paid the fine, but not the compensation.

On 15 September 2015, the Federal Court found that Thomson had contravened ss 285, 286 and 287 of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth). On 15 September 2015 the Federal Court imposed an aggregate penalty of $175,550 on Thomson and also ordered him to pay compensation of $231,243 and pre-judgment interest of $146,937 to the HSU.

On 11 October 2016, Thomson applied to the Law Society of New South Wales for a practising certificate. His application disclosed “theft of between $3500 and $5500 from employer” and sentence by way of a “fine of $25,000”, but did not disclose the contraventions of the Workplace Relations Act.

On 19 December 2016, the Law Society Council notified him of its refusal to grant a practising certificate on the basis of his criminal convictions.

On 23 February 2017, the Law Society informed the Prothonotary of the Supreme Court of NSW of that refusal.

By summons filed on 15 March 2018, the Prothonotary applied for declarations that Mr Thomson has been guilty of professional misconduct, is not a person of good fame and character, and is not a fit and proper person to remain on the roll of legal practitioners of the Supreme Court.

At common law, the Supreme Court of NSW has an inherent jurisdiction to control and discipline lawyers admitted or operating within its jurisdiction.

Section 264 of the Legal Profession Uniform Law provides as follows:

264 Jurisdiction of Supreme Courts

(1) The inherent jurisdiction and powers of the Supreme Court with respect to the control and discipline of Australian lawyers are not affected by anything in this Chapter, and extend to Australian legal practitioners whose home jurisdiction is this jurisdiction and to other Australian legal practitioners engaged in legal practice in this jurisdiction.

(2) Nothing in this Chapter is intended to affect the jurisdiction and powers of another Supreme Court with respect to the control and discipline of Australian lawyers or Australian legal practitioners.

In deciding whether to remove a lawyer from the roll of legal practitioners, “the ultimate issue is whether the practitioner is shown not to be a fit and proper person to be a legal practitioner of [the] Court” as “at the time of the hearing”: A Solicitor v Council of the Law Society of New South Wales (2004) 216 CLR 253; [2004] HCA 1 at [15], [21].

In determining such an application, the Court must satisfy itself that any orders made are appropriate in all the circumstances, even if the proceeding is uncontested: Prothonotary of the Supreme Court of New South Wales v Livanes [2012] NSWCA 325 at [27] (McColl JA). The Court should also make appropriately detailed factual findings, both to advance public confidence in the control and discipline of the profession and to assist those tasked with determining any future application for readmission: Bridges v Law Society (NSW) [1983] 2 NSWLR 361 at 362 (Moffitt P); New South Wales Bar Association v Cummins (2001) 52 NSWLR 279; [2001] NSWCA 284 at [24] (Spigelman CJ, Mason P and Handley JA agreeing); Council of New South Wales Bar Association v Power [2008] NSWCA 135; (2008) 71 NSWLR 451 at [9]–[11] (Hodgson JA, Beazley and McColl JJA agreeing).

In New South Wales Bar Association v Cummins (2001) 52 NSWLR 279; [2001] NSWCA 284 at [20], Spigelman CJ identified four “interrelated interests” which may be regarded as protected by such proceedings:

“Clients must feel secure in confiding their secrets and entrusting their most personal affairs to lawyers. Fellow practitioners must be able to depend implicitly on the word and the behaviour of their colleagues. The judiciary must have confidence in those who appear before the courts. The public must have confidence in the legal profession by reason of the central role the profession plays in the administration of justice. Many aspects of the administration of justice depend on the trust by the judiciary and/or the public in the performance of professional obligations by professional people.”

The Court held that three principles were particularly relevant to the determination of the application:

The Court found that Thomson’s conduct whilst National Secretary of the HSU included theft and other misappropriation of funds belonging to the HSU and abuse of a fiduciary or a quasi-fiduciary position, in each case over an extended period which involved “significant and prolonged dishonesty for personal gain”.

Furthermore, the Court noted Thomson had not suggested that he had undergone a period of reformation of character since his time at the HSU, and he had failed to disclose all of his convictions to the Law Society Council or pay the penalties imposed by the Federal Court.

For these reasons, the Court found that Thomson was not a fit and proper person to remain on the roll of lawyers, and his name should be removed from the roll.

This case demonstrates that even when misconduct occurred a long time ago and was not in connection with legal practice, it can still lead to a conclusion that someone is not a fit and proper person to engage in legal practice. In this case, Thomson’s misconduct involved dishonesty on a large scale over a long time, and his lack of candour to the Law Society Council also weighed against his fitness to practice.

Finally, this case also demonstrates the difference between the ethical standards of the union movement and the legal profession. The union movement and the ALP were (at least for a time) willing to tolerate Thomson’s dishonest misuse of HSU funds, whereas the Supreme Court of NSW held that such conduct was inconsistent with being a lawyer.